How to build the perfect pile of snow

As the Sochi 2014 Olympic snowboard and ski-cross courses are revealed, we take a look at how the magic happens with an inside peek at snow park design.

PEMBERTON, B.C. — Tucked in between a big sky and mighty mountains, just north of Whistler, sits Pemberton, B.C. The small town of roughly 2,000 is home to adventurers, expats, young families – and one of Canada’s top course designers.

It’s a gorgeous, balmy fall day with trees streaked in okra and orange. Steve Petrie, in black specs and short sleeves, is moving dirt at the Pemberton BMX Track, converting the start hill into a drop-in for a snow skills park.

He’s got two and a half days to finish the job. As the owner of Arena Snowparks, he’s also busy planning the 2013/14 season, and come the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics, he’ll be heading east for more work.

But it takes more to ruffle this 42-year-old mellow Ottawa native, who’s built and designed pipes, snowboard cross and slopestyle courses for events such as the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympic Games, the World Snowboarding Championship and the Arctic Challenge.

Petrie, tanned with slight stubble, sits down for a coffee break to shed some light on what it takes to build an Olympic course, and if there is ever such a thing as enough snow.

OUT OF DIRT

He got his start back in 1994, when Whistler Blackcomb got one of Canada’s first terrain parks. Petrie, who’d taken a job grooming so he could spend his days snowboarding, began venturing into the park to build some jumps. There were no manuals or how to’s, which was a great thing, he says.

The thumb of rule was, “build it, open it up the next day, see if people like it – great. If they didn’t, we’d just change it up,” Petrie explains.

As a competitive snowboarder, he was out hitting jumps continuously, and getting an eye for park construction.

“I think I had a big role in that whole progression because I was just out there every night trying to figure it out on my own,” he says.

Petrie raced for about four years, competing in a few World Cup races and the North American Boardercross Series in Whistler.

“Every year, I would get better and better, and I would do things a little bit different until we got to the point where it’s like a, not standard, but best-of-practices for building jumps,” he says.

“For an average jump, you’ll probably need anywhere from like 2,500 to 5,000 cubic meters of snow .”

Fast-forward till 2013 and park construction has gone high tech.

Lucas Ouellette, project manager at Arena Snowparks, stands in the factory shop, a seven-minute drive outside Pemberton. It’s here in the spacious, light warehouse, among welding guns, paintbrushes and all sorts of tools that magic is done. New, shining rails and boxes are designed, tweaked and produced.

“It’s all coming down to a science now, where we almost don’t waste any time anymore. We’ll come in and know exactly how much snow’s needed to build a certain jump,” says Ouellette.

“For an average jump, you’ll probably need anywhere from like 2,500 to 5,000 cubic meters of snow so if you times that by four, five jumps by 1,000 cubic meters and then the rails take a little bit less,” estimates Petrie. You get the idea.

Yet, “as soon as you plan a major event, there are lots of things that go sideways,” he says and smiles knowingly.

RAINCOUVER 2010

The Winter Olympics in Vancouver 2010 may go down as the event that put Canadian athletes on the world map. But, it may also be remembered as one of the wettest Olympics in modern times.

Just the very thought of building the halfpipe makes Ouellette crack up. “It was terrible,” he says.

“There’s nothing, they’re bringing a helicopter from one side of the mountain, they had an excavator loading up buckets – this huge Sikorsky helicopter pick it up, drive it over, dump it and we had to push it into place.”

Even so, there wasn’t enough snow to go around.

“We’re hardly driving snowcats around the halfpipe anymore because there’s so much mud everywhere and the snow’s only a foot deep in most places,” he says. “We’re actually going into the forest with buckets, filling up buckets with snow to build the drop-in.”

Ouellette is still amazed.

“It worked,” he says. “From what people could see, everything looks white. They don’t see all the hay bales underneath, the scaffolding, plywood lining the sides of the halfpipe just to hold the walls together.”

But let’s return to January 2010, when Petrie arrived to Cypress to build his first Olympic halfpipe. It poured and grass grew in the pipe. “Oh, this is going to be really iffy,” he thought to himself.

At his hands, he had the largest crew he’s ever worked with: 20 people from his own company (four machine operators and 16 handshapers), and 100 volunteers. Not to talk about the brand-new snowcats and the helicopters.

Petrie calls the Olympics, “the pinnacle of building,” where you get what you need to get the job done.

“The show must go on, no matter what,” he says. “You have to put together your A team, knowing that whatever Mother Nature throws at you, you have to build the pipe.”

DREAMING OF A WHITE CHRISTMAS

What saved Petrie and his crew, in the end, were two blessed weeks in December.

“We got lucky, they were able to make a bit of snow for us kind of early in the winter before the warm, wet weather hit so basically we just protected that pile of snow,” he says. “It turned out to be just enough to build the pipe but we had to be really careful what we did with it, couldn’t waste any of it.”

Necessity is the mother of innovation as the old cliché goes, and Petrie ended up developing a whole new technique for building pipes.

“It was the most perfect pile of snow I’ve ever made.”

“Like a typical halfpipe build, a lot of snow gets pushed out at the bottom, it’s part of the process but we didn’t push anything out of the bottom, we kept it all in the pipe,” he explains.

The crew used a laser, which sat at the top of the pipe. It could shoot a beam either on a horizontal or a vertical plane.

“We built one wall of the pipe and we shot the laser down so that we knew exactly how high we needed the snow so we could push, push, push,” Petrie says and shows the imaginary build with his hands. Then, they did the exact same thing with the other wall.

“You ended up with a pipe that was literally within ten centimeters height all the way down, it was really perfect. It was the most perfect pile of snow I’ve ever made,” he concludes with a laugh.

PAST ITS GLORY DAYS

Since then though, halfpipes have become somewhat of endangered specie. As well as those who build them.

Petrie, who’s built numerous pipes during his 11 years in the business, finds that, “the younger, up-and-coming generation,” isn’t as interested as it used to be. Instead, they’re going for the jumps and the rails.

Building pipes isn’t cheap and with no one riding them, the resorts are no longer keen on picking up the tab for dirt work and snowmaking. Fewer pipes equal fewer course builders, with “a knack for doing it and patience,” notes Petrie.

Part of the reason behind halfpipes’ decline in popularity goes back to the early days, he says, when many resorts invested a lot of money into pipes but didn’t have the right people building it. Since the pipes got poorly built, people didn’t bother with them and put their energy on the slopes elsewhere.

But shed no tears. According to Petrie, we’re just going through a cycle.

“I can see it coming around again,” he says, bringing up his ten-year-old son as an example. “Maybe, some day, it’ll come back when he gets to that age and wants to ride a pipe.”

HANG TEN

While pipes might be in for a temporary slump, slopestyle will make its Olympic debut. But participating in the Winter Olympics has also initiated a debate about whether men and women should compete on different courses, instead of on the same ones as they currently do.

Petrie fancies the idea of having separate courses, but not sure it’ll ever happen the way things are currently set up. It’s always a challenge to try and build a course that meets the needs of both groups since they’re looking for different sized jumps, he says.

One idea, however, would be to adjust the course during the actual event.

“It would be cool if maybe we had a gap where men could go first,” Petrie says. “And then there’s kind of two-three days before the women start and we could push the jumps a bit closer to reshape the course.”

In the meanwhile, he is taking advantage of the current trend of jumps becoming, not bigger, but shorter, which gives the athletes more hang time to execute their tricks.

“What we’re trying to do is kind of on that same concept of building the jumps not longer, but higher with more shape and more landing so women can go and hit it and land 50 feet,” Petrie says.

“They’re still going to hit transition but the landing is long enough that men can go 65 or 70 and still hit a nice landing transition.”

WEATHER ON MY MIND

Anders Forsell, who’s the head designer of the slopestyle course at Sochi, shares the same mindset.

“Every jump will have two different take offs featuring different lengths for men and women,” he says.

“We’re dealing with nature and it can play strange tricks.”

Forsell won’t reveal the exact size of the jumps just yet since it will depend on when and how much it snows.

“We’re dealing with nature and it can play strange tricks,” says Roberto Moresi, FIS snowboard assistant race director. He works closely with Forsell and Davide Cerato, of the Sochi 2014 Olympic and Paralympic Organizing Committee, on developing the Olympic halfpipe and slopestyle courses.

Moresi describes last year’s snowless winter, which resulted in February’s slopestyle test events being cancelled, as “abnormal.”

“The year prior we had some other events, which were hammered by snow falls,” he says.

If worst-case-scenario happens, meaning no or little snow, Moresi says the team got their strategy clear: “minimize the snow production and maximize the ground work.”

In the end, it’s all about giving the riders and skiers an opportunity to perform at their best, offers Forsell, “so that we get a good show.”

Moresi, a snowboard veteran and once a member of the Italian national team, finds that when it comes to course development and athletic performance, “it’s a hand-in-hand progression.”

“As we improve the construction, they improve their riding and that’s what they’re asking for,” he says.

KEEPING UP

For moguls, the opposite case is true.

The courses have pretty much looked the same for the last 20 years, with only a small number of changes, explains Peter Judge, CEO of the Canadian Freestyle Ski Association.

“I think the athletes have stepped out of it a bit, just because the courses have not gone way steeper or way longer,” he says.

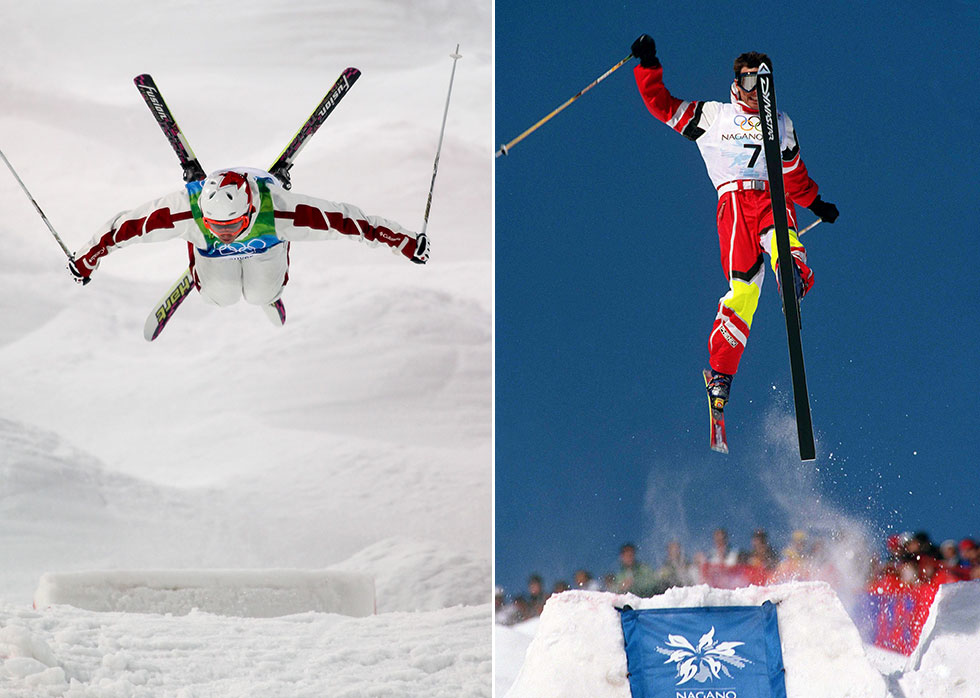

At left, Alex Bilodeau is seen during competition at Vancouver 2010. At right Jean Luc Brassard competes during Nagano 1998.

“It’s kind of stayed in that one narrow bandwidth of what the course can be.”

The actual moguls have changed though, with the courses going from being man-made to snow-cat made, which has produced a very even rhythm, notes Judge.

Add to the fact that the skis being used are significantly faster compared to ten, 15 years ago.

Nowadays, mogul skiers are going almost ten meters per second, covering up to three bumps a second.

“It’s very, very fast and with top guys, it’s mind-boggling how quick it goes,” Judge says.

OLD TECHNOLOGIES REVISITED

Flynn Seddon is the president of B.C. Snowboard Association, and the technical representative for 2015 Canada Winter Games. This summer, he worked with Canadian course designer Jeff Ihaksi up at Tabor Mountain in B.C.’s Prince George.

They spent two and a half months building dirt shapes for the snowcross and the slopestyle courses, such as the actual course line, jumps and corners.

“It’s not a new concept, it’s an old concept but we revisited it,” he says.

The idea behind by the extensive pre-shaping out of dirt is to make the courses a bit more permanent in order to cut down on future costs.

Seddon compares it to a Formula One circuit, where, “you have the specific track built, that’s the shape of it, that’s the way it works.”

He argues that hundreds of hours of cat time are spent building Olympic-sized courses, which are used for perhaps one weekend or a week, only to be bulldozed down afterwards. Next time, there’s an event on, the whole process has to be repeated all over again.

According to Seddon, the concept is being reviewed at FIS world level as something that could potentially be used for future Olympic and world cup courses.

For him and Ihaksi, the goal is to use the technique at the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics in South Korea.

“We’re hoping to get in there, hopefully be the guys that build the Olympic course out of dirt for guys,” he says with an infectious belly laugh. “We’ll see what happens.”

But first there’s Sochi.

SEARCHING FOR SOCHI

For his second consecutive Winter Olympics, Petrie says that the set-up will be a lot different.

“The Russians are not hiring one company to take care of one thing. They’re just bringing in people from all over the place so I’m more of a hired guy instead of the guy in charge,” he says with a smile. “It’s all friends of mine that are doing work there so it’s not so bad.”

He will be working with Swedish course builder David Ny on the boardercross and ski cross course.

When Ny came on board four years ago, the idea was that there would two separate courses but with a shared start. Then, ski cross had a change of heart.

CROSSING OVER

“Now, they’ve decided to race in my course, which is quite fun,” he says. “Plus, it saves snow.”

Eighty to 85 per cent of the course is pretty much the same, except that the ski cross racers make a turn, only to be reunited with boardercross for the last third of the course.

Ny, who likes to build freestyle-like with lots of air time and quite steep kicks, says it’s hard to build jumps for ski cross since it’s so much faster than boardercross.

“But it feels like we’ve found something that’s going to work for both groups,” he says.

Eighty to 85 per cent of the course is pretty much the same, except that the ski cross racers make a turn, only to be reunited with boardercross for the last third of the course.

“What we’re doing on some of the jumps that we know are going to be really fast, is to build so-called ‘camel landings’, which are two landings,” Ny continues. “If you don’t time either the first or the second landing, you’ll end up on a hump, which is no good, but it’s the only way to build the course.”

Another positive is that these types of landings will work with the Sochi forecast, no matter if it’s dumping or pouring.

That’s a good thing since the weather is a bit of worry. Ny, who helped Petrie building the Olympic halfpipe at Cypress, says Sochi has some striking similarities such as the amount of precipitation it receives.

But Ny is not one to worry. “We just have to cross our fingers,” he says.

What’s Petrie’s word on battling the Russian snow gods? “It may be a complete challenging event but we’ll have a good time, I’m sure.”