Play as you are: Olympians set positive goals for LGBTQ in Canadian sport

The news: On Tuesday the Canadian Olympic Committee announced plans to foster LGBTQ inclusivity in national sport. The #OneTeam Athlete Ambassador program will hit schools to speak about mental fitness and equality, supported by a first-ever school resource on LGBTQ issues. Egale Canada, the foremost national charity promoting LGBTQ human rights, is on board to guide all programs and resources. Plus, a partnership with You Can Play rounds out a great top line. In good form, the COC is also taking care of its own house. The Committee added language to its by-laws and is training staff to create a highly-inclusive corporate culture.

If you think today’s new partnerships, enhanced resource, and #OneTeam program is a positive step for LGBTQ equality in Canadian sport, you’re not wrong.

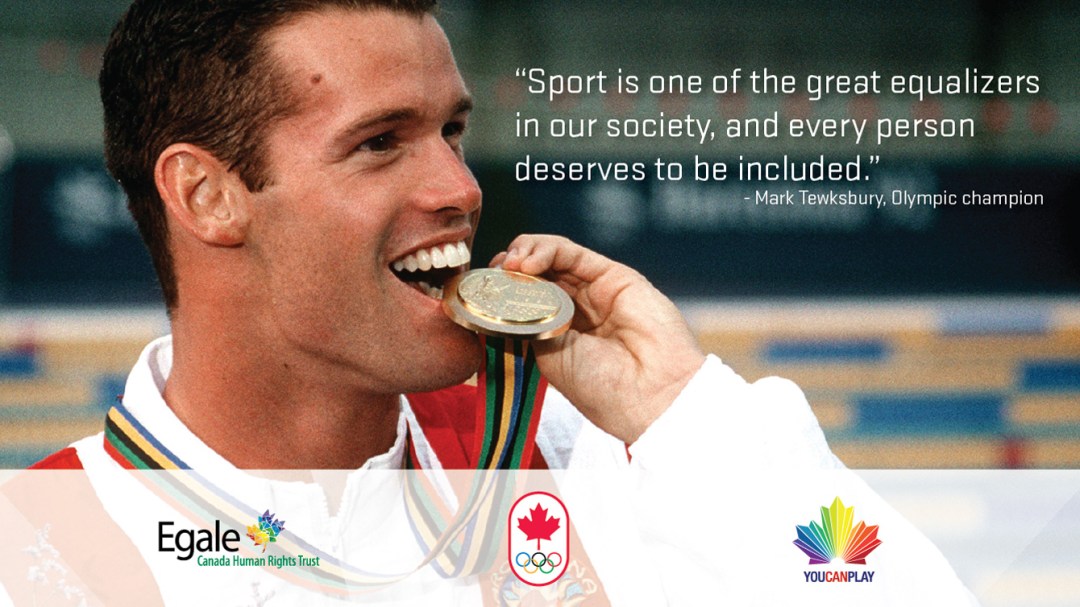

“Sport is one of the great equalizers in our society, and every person deserves to be included regardless of the level of competition.” – Mark Tewksbury, three-time Olympic medallist

Yet it’s all a silver lining and here’s why: although athletes in Olympic and high-profile sport are coming out publicly in greater frequency, their stories tell us the path to liberation was prickly, longer than it should have been, and had dramatic affect on their performance.

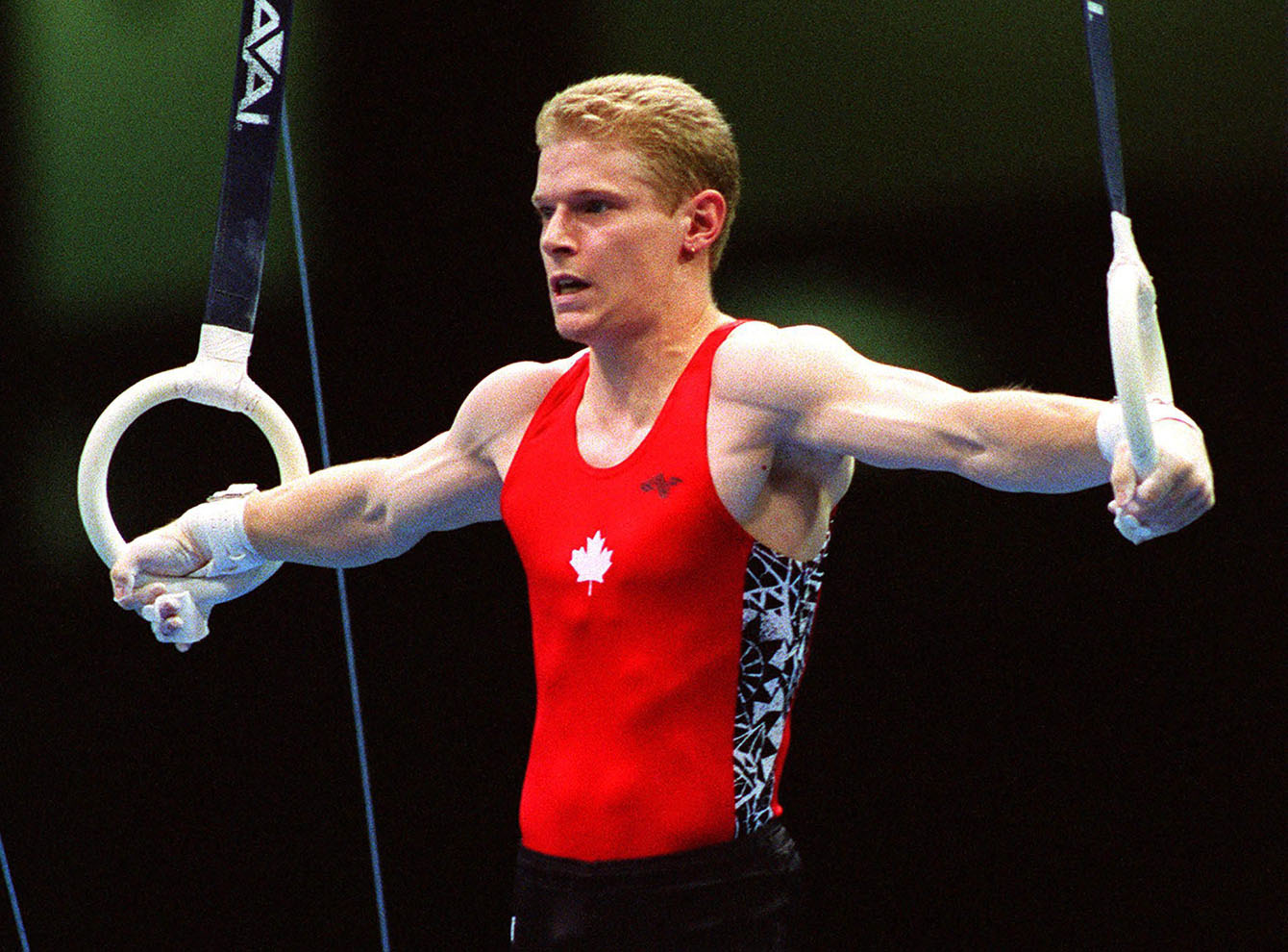

Kris Burley is now a project manager but he was once an Olympic gymnast who spent the entirety of his 10 years on the national team in the closet. “I wasn’t out as an athlete, I was in a relatively hostile environment,” recalls Burley, who once had his nose broken so badly by a teammate he had to be hospitalized.

After the 1996 Olympics, Burley saw international competitors persecuted, even penalized by judges for their sexual orientation and firmly decided he wouldn’t be one of them.

After the 1996 Olympics, Burley saw international competitors persecuted, even penalized by judges for their sexual orientation and firmly decided he wouldn’t be one of them.

Now 15 years after retirement, Burley believes the sport community is “well behind other areas” when it comes to LGBTQ acceptance.

I think there is a tremendous amount of work that has to be done to enable all athletes to achieve their absolute best – Kris Burley, Olympian

Russian laws restricting gay rights were brought into focus because of Sochi 2014. In October 2013, the United States Olympic Committee extended their non-discrimination by-law to include sexual orientation. In mid-November of this year, the IOC included the same idea among 40 recommendations to be voted on by all members in early December.

Openly gay speed skater Anastasia Bucsis supported the movement at her second Olympics while in Sochi. “It just felt morally correct for me,” she says. “I felt as though I was standing up for what was right. I knew that going there and not lending my name to this cause I would regret it.”

She doesn’t want to be known as the ‘gay athlete’ but she is helping because of a personal promise she made during the deep cold of a Calgary winter in 2012 – back before anyone knew. “It was hard. I was so anxious. I was so lonely and confused it definitely affected my life on and off the ice and it affected my results,” Bucsis points out.

She isn’t alone when it comes to sport performance being gravely impacted, but at least she made it to the Olympics. Hindered by the stress of hiding himself, 2011 Pan Am Games silver medallist kayaker Connor Taras missed the 2012 Olympic team by just six-tenths of a second (0.6).

She isn’t alone when it comes to sport performance being gravely impacted, but at least she made it to the Olympics. Hindered by the stress of hiding himself, 2011 Pan Am Games silver medallist kayaker Connor Taras missed the 2012 Olympic team by just six-tenths of a second (0.6).

“I was so miserable. I really had to sit down and figure things out,” reflects Taras on the time after missing the team. “One of the biggest things was I had to fix my personal issues because I was wasting way too much energy on things that weren’t related to sport, being in the closet.”

In the year after coming out Taras improved on his eight-year-old personal bests and finished on the podium twice at nationals. The 25-year-old is looking ahead to the Toronto 2015 Pan American Games and Rio 2016, more himself than the last time he took a shot at the Olympic Games.

It seems when an athlete comes out they do it for themselves, but they hide because of us. Kris had hostile teammates, Anastasia a “Christian, conservative” upbringing, and Connor the male kayaker image.

So they wrestle with their sexual identity, what it means, and how to express it. Something that is only a fraction of what makes up an athlete is magnified inside locker rooms and on the field of play, by those LGBTQ or not, because sport is still behind in realizing the magnifying glass is two-way. We all need to ‘figure things out’ like Connor did.

“It’s an issue until it’s a non-issue,” says Bucsis. “This isn’t just a gay issue, everyone goes through those struggles of accepting themselves. It doesn’t matter your orientation, we’re all in this together.”