Concussions: Better guidance for Canadian athletes impacted by invisible injury

A separated shoulder. A broken wrist. A torn hamstring. A sprained ankle.

They are among the many injuries suffered by athletes, easily noticeable because of the sling, cast, brace, walking boot they’re wearing. They’ll walk with a limp. They’ll wince when there’s an awkward movement.

For athletes sustaining a concussion, the signs of being injured aren’t nearly so obvious.

What is a concussion and its symptoms?

A concussion is a complicated process that occurs in the brain following a traumatic event which transmits an impulsive force to the head. While we don’t typically see physical damage from a concussion on standard medical imaging, we know that it does alter the way the brain functions.

It’s the invisible injury.

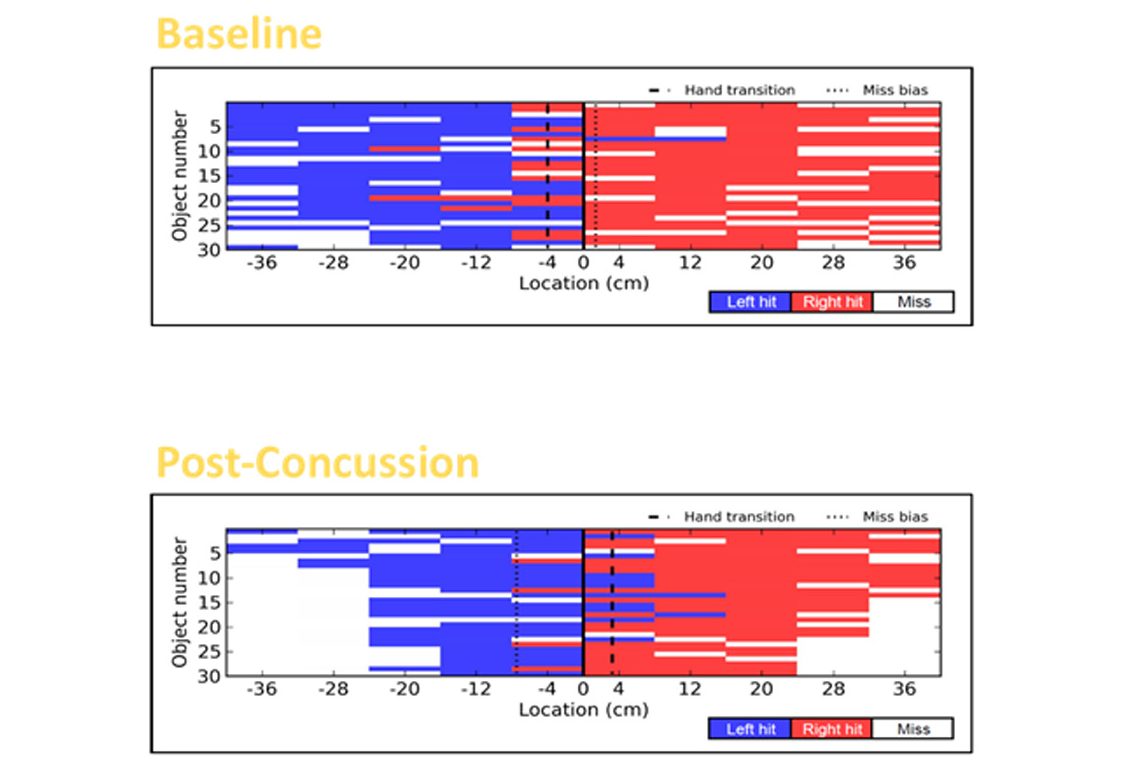

In the Object Hit Task, an athlete is asked to hit targets using the left and right arms of the KINARM robotic technology. In the baseline assessment (top), 77% of targets were hit, with speeds of 40.48 cm/s on the right hand and 36.01 cm/s on the left hand. In the post-concussion assessment (bottom), only 63.3% of targets were hit. with slower speeds of 21.33 cm/s on the right hand and 20.44 cm.s on the left hand. Graphic courtesy of Benson Concussion Institute/Canadian Sport Institute Calgary

In some cases, it can be quite obvious to recognize if there is a loss of consciousness, seizure activity or convulsions, vomiting, agitation or combative behaviour, confusion, stumbling, balance or gait difficulties. In other cases, the warning signs may be subtle, such as a blank or vacant stare, slow to get up, difficult responding to questions, or slurred speech.

The signs and symptoms of concussion may present immediately following the injury, or may take minutes to hours, and sometimes, days to appear. When the brain is not functioning properly, athletes who continue to participate in sport and do not seek proper care may be at risk of a prolonged recovery, additional injury, or even complications later in life.

The brain is your command centre and you’re going to need it forever. So it needs to be treated with respect from the outset of injury through recovery.

What is being done about concussions in Canadian sport?

Making sure Canada’s Olympic, Paralympic and high-performance athletes are healthy is why the chief medical experts at the Canadian Olympic and Paralympic Sport Institute (COPSI) Network, Own the Podium (OTP) and the Canadian Olympic Committee (COC) have collaborated on comprehensive and standardized guidelines to provide world-leading health care provisions for the athletes, coaches, staff, and officials in our country’s sport system.

All Canadian national teams will use these guidelines, implemented after 18 months of review and revisions by the above organizations as well as team physicians from national sport organizations, physicians from the Canadian Academy of Sport and Exercise Medicine, and Parachute Canada, a national charitable organization dedicated to preventing injuries.

READ: Sport-Related Concussion Guidelines for Canadian National High-Performance Athletes

Our number one priority is the health and safety of the athletes. We want to have a standardized process for our high-performance athletes from preseason education and baseline assessments through to onsite medical assessment, individualized management, and safe return to sport. No matter where an athlete gets injured, they are going to get the same standardized approach to concussion management.

A key component of the guidelines is educating all those who work closely with athletes. Each national team has an integrated network of support staff – doctors, physiotherapists, experts in strength and conditioning, physiology, nutrition and mental performance – that assist coaches and athletes in the daily training environment. Together they provide a team approach to the total health and well-being of the athletes to augment performance.

National teams will also put their athletes through what medical experts refer to as “comprehensive intake” prior to the start of the competitive season. They will undergo medical assessments and discuss their medical history, including specific information about their past concussions. Doctors and their multi-disciplinary support team perform a multitude of concussion clinical assessments to really get to know the athletes subjectively and objectively at an individual level when they are healthy and uninjured.

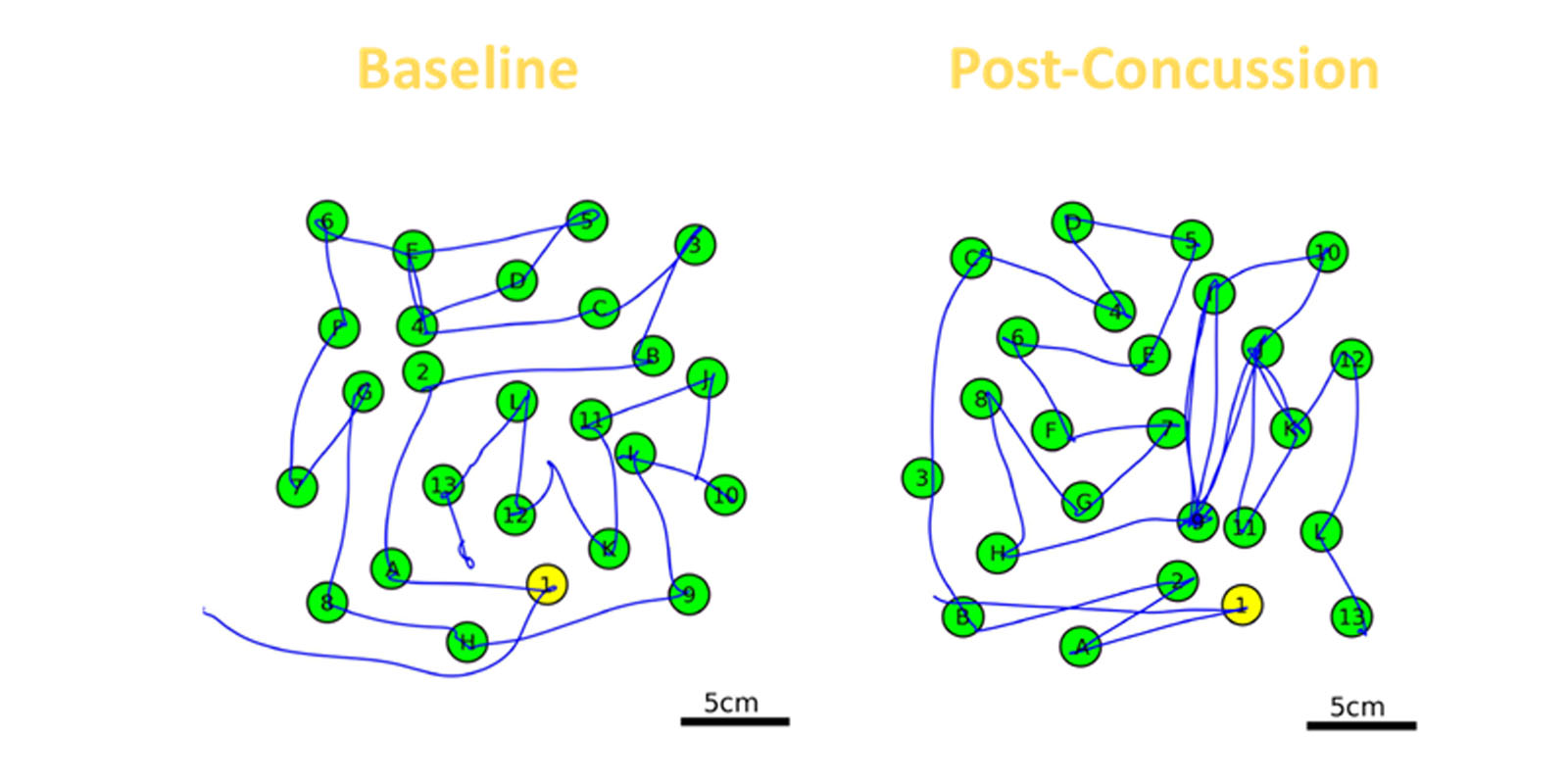

In the Trails B Neurocognitive Task, an athlete is asked to connect numbers and letters in chronological order. In the baseline test on the left, the total task time was 31.62 seconds. In the post-concussion test on the right, the total task time was 80.02 seconds. Graphic courtesy of Benson Concussion Institute/Canadian Sport Institute Calgary

The “getting to know” piece is an important one in identifying that an athlete may have suffered a brain injury during training or competition – especially given the invisible nature. Suspecting an injury is the first step. All stakeholders have a role to play in that. Early identification and prompt intervention with targeted, individualized management strategies are clinically important to potentially shorten the duration of this injury.

High-performance athletes, not surprisingly, want to return to competition as quickly as possible. There may be misconceptions of the athlete that symptom resolution means they are recovered. It is now recognized that the window for physiological recovery typically outlasts symptom recovery.

There’s additional pressure to push the envelope when an injury interferes with preparations for a national championship, a world championship, an Olympic or Paralympic Games. Increased education around concussions – combined with improved techniques in medicine and science to assess and treat brain injuries – are helping to convince athletes and their support teams that a complete recovery has short and long-term benefits for both performance and health.

It can be very hard on athletes, who can get lost in the present moment when they’re injured. They start looking at the calendar for their upcoming competition and may feel that they will lose their competitive edge, which can make symptoms worse due to the anxiety this creates.

Athletes are always striving for the one per cent performance gains that will make their podium dreams become reality. But it is important for them to understand that the subtle deficits of a concussion, if missed, may have grave consequences in a high-risk sporting context.

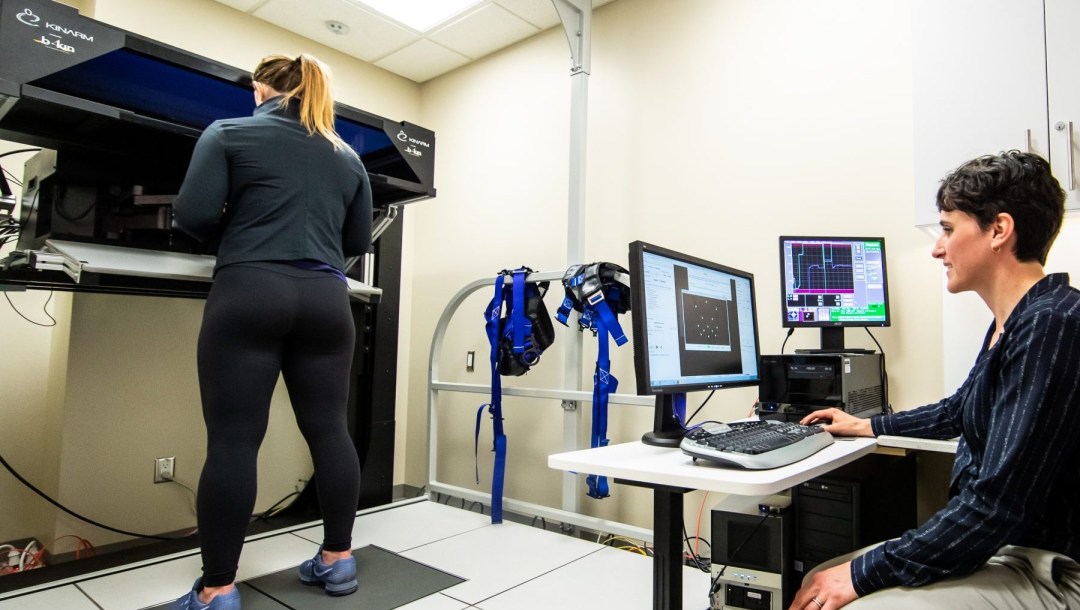

Team Canada wrestler Erica Wiebe undergoes an assessment on the KINARM robotic technology which allows experts to compare an athlete’s brain function when healthy against their post-concussion results. Photo: Dave Holland

Through OTP-supported applied concussion research and innovation projects, our precision to reliably and objectively ascertain physiological recovery and readiness to return to sport following a concussion is improving with the use of novel robotic technology and assessment techniques.

Physiological recovery is not only essential for a successful return to high-performance sport, but to reduce an athlete’s risk of further, potentially catastrophic, injury.

When athletes and their support team understand this, knowing that we are doing everything possible to accelerate recovery using objective measures puts them at ease.

Everyone involved in an athlete’s career needs to remember that while we want them to be at their best when representing their club or country in competition, it’s more important to understand they will need their brain for the rest of their life.

Dr. Brian Benson is the Chief Medical Officer at the Canadian Sport Institute Calgary and Medical Director of the Benson Concussion Institute.