Bruny Surin: Unwavering support but inevitable stress as an Olympic hopeful’s father

I remember the first time Katherine brought up track and field.

She was five years old. She saw me run and compete and she asked me to put her into a track club. Hold on a minute!

I told her she was too young, but she insisted. So, I told her, “Listen, it’s too soon. When you turn 14, if you still want this, I will sign you up for a track and field club.”

What do you think happened?

We were on vacation in Florida when she turned 14. Usually we goofed around with each other, but here, she was always in a bad mood. For days, she wouldn’t speak. One day, her mother took a walk with her. When they returned, my wife told me I’d need to speak to my daughter.

I went outside and she was waiting for me in the parking lot. She cried and cried and cried. When I asked what was wrong, she told me, “I don’t want to play tennis anymore. It’s not my passion. Running is what I want to do.”

Just like that. Boom.

I couldn’t believe it and I made it into a joke: if she didn’t want to play tennis anymore, it would cost me way less!

I asked why she was crying like that. She told me she thought I would be disappointed. After all, she was a junior national team hopeful. I told her, “I would never be disappointed in you. It’s your life, your career. I’m your dad, I’ll always be there to support you.” That’s how she started track and field.

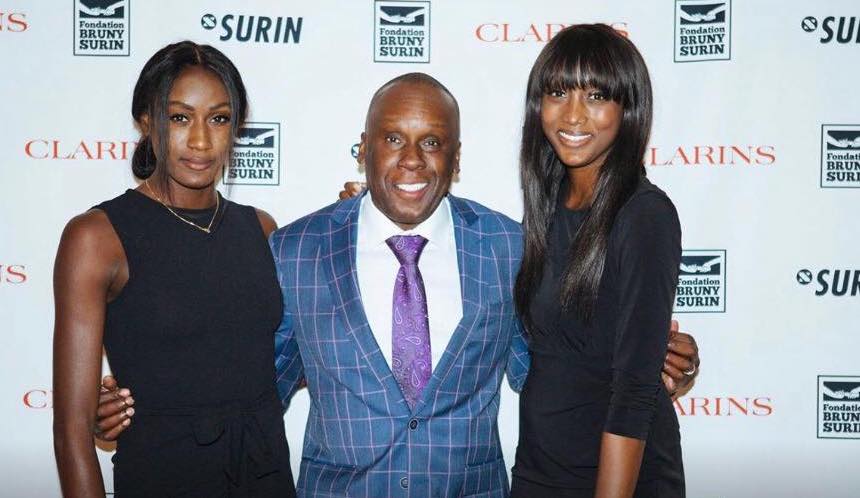

From left to right: Bruny Surin, Katherine Surin and his wife Bianelle Legros. (Photo courtesy of Katherine Surin)

It was clear from the beginning, both for her and her sister, that I would never want to be their coach. I never wanted to mix the two sides – Dad and Coach. It would be too much for my heart to take!

I’ll be Dad, their biggest fan. If they need advice, they can ask. And I’ll be there at practices and competitions, but I don’t want to impose.

I’ve seen parents impose – impose things on their children, impose their advice. I know the result; it’s irritating to the child. I didn’t want to irritate my daughter.

I remember one of her first big competitions. It was the 2013 Canada Games in Sherbrooke. I was in the stands, but I knew she was warming up. I decided to go watch the warmup in case she needed me. I went in and approached her. The look she gave me! It was like, “what are you doing here?!” I turned right around.

Afterwards, it was something I always respected, even the morning of the Canadian Championships − which would ultimately determine who would represent Canada at the World Athletics Championships in 2019.

I ran into her at home. She had been stressed for days. I felt it. It was palpable. I asked myself, should I wish her good luck, give her a pep talk, leave her alone? Finally, I went to her and just gave her a high five.

It’s the most difficult thing about having an elite athlete for a daughter – the stress.

Hers, which affects me directly, and the stress I feel sitting in the bleachers during one of her races. I see the stress and pressure in her expression and it’s like she’s sharing her emotions without intending to.

When the girls started competing, I understood why my mother never watched me compete live while I was racing. The pressure is insane! I didn’t think I would be nervous like that. I’m a professional! But it gets to you, it’s crazy.

You always hope, as a parent, that your children flourish and they perform, but it’s nerve-wracking. I don’t think it will get better with time. She has very serious goals and they’re not easy to obtain.

I know that she’s under pressure because of her last name, because people talk and they make comparisons. Even in tennis, we heard that Bruny Surin’s daughter was playing, that she’d be fast, she’d learn fast, etc. On my end, and no matter what sport she was playing, I made sure to never put that pressure onto her. I always said, “Do it for yourself. As long as you’re having fun, you’re doing your best and you’re taking it seriously, it’s all good for me. The rest is just a bonus.”

It was only when she and her sister started playing sports that they learned that their dad went to the Olympics, that he did this and he did that. Once, I went to speak at a conference in Katherine’s class. When I came in, all the students clapped. I noticed that she was giving me this weird look. She asked me after why they clapped for me. It was then that I realized, when I came home, I wasn’t Bruny Surin the athlete, the Olympian. I was just Dad. That’s when I started to tell them stories of my career, at the risk of being told, “Yeah, but that was back in your day!” Ouch.

From left to right: Katherine, Bruny and Kimberley Surin. (Photo courtesy of Bruny Surin)

Katherine went back to Europe a few weeks ago to start training again, after spending the summer at home. She has her eyes locked on Tokyo. We don’t know what the future holds for her, as is the same for many summer athletes. I want to tell her even more: “Trust yourself”. That’s not dad talking, but the observer in me. Sometimes people have so much potential but they never uncover it. As soon as she discovers it and believes in it 100 per cent, it will be like night and day.

From now and for the rest of her career, I will always be there, somewhere in the bleachers, stressed, but above all, so proud.

Bruny Surin is a four-time Olympian who won gold at Atlanta 1996 as a member of the 4x100m relay. He is also a two-time world champion in the 4x100m relay and and two-time world silver medallist in the 100m. He has been a co-holder of the Canadian 100m record of 9.84 seconds since 1999. In 2019, his daughter Katherine won 400m bronze at the Canadian Championships and competed at the NCAA Division 1 Championships for the University of Connecticut.

– Originally told in French to Camille Laventure