Road to Paris 2024: Three Olympians reveal big goals ahead, key lessons learned, and why representation matters

The next Olympic Games are less than a year and a half away.

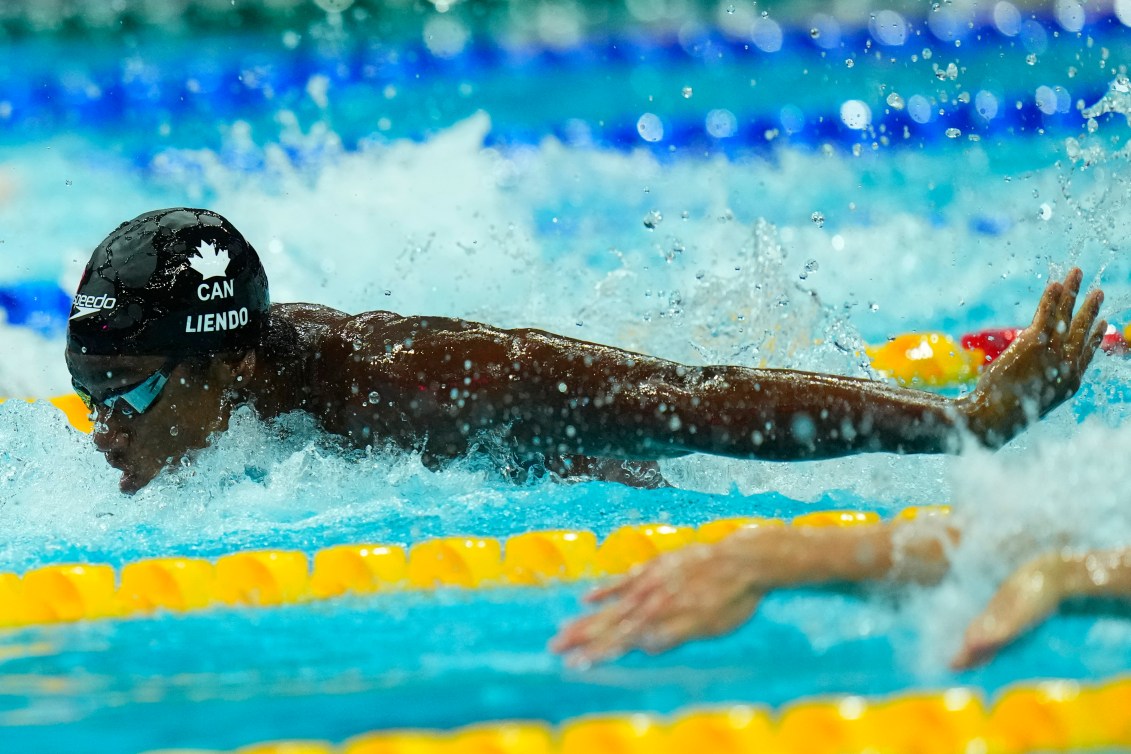

Beach volleyball player Brandie Wilkerson, diver Cédric Fofana, and swimmer Joshua Liendo all have their eyes on the big prize – earning their way back to the world’s grandest sports stage.

For all three, there were plenty of lessons to be learned from the highs and lows they experienced at Tokyo 2020 and elsewhere. They’ll be putting some to use this year as they embark on their journeys towards Olympic qualification once again.

But what they do on the sand or in the water isn’t the only thing that is important to them.

Throughout the year, we’ll check in with each athlete to catch up on the exciting developments in their lives and careers. As February is Black History Month, we took this opportunity to talk about the value of representation – especially in sports which have not traditionally been known for their diversity.

Brandie Wilkerson: Reconnecting with her roots

In her Olympic debut, Wilkerson had high expectations for herself and veteran partner Heather Bansley. Elimination in the quarterfinals was not what they had envisioned.

Despite that disappointment, Wilkerson says she did learn how strong she really is as she navigated the abnormal and extra stressful nature of an Olympic Games happening amidst a pandemic.

That strength was important as she and Bansley came to the realization that they had different goals for the future. While Bansley retired to become a NextGen coach, Wilkerson teamed up with Sophie Bukovec, giving her a new challenge to tackle.

“I felt like I wanted to put myself in a position to be a leader and to create a team in my own fashion and just really put myself out there to see if I can do this all over again, almost starting from scratch,” said Wilkerson.

It was a difference experience, for sure, as she and Bukovec had to play in qualifiers to get into the main draws of tournaments. However, they clicked quickly, highlighted by winning the silver medal at the world championships.

But then an opportunity came that Wilkerson couldn’t pass up.

Melissa Humana-Paredes, Wilkerson’s old teammate at York University, and her longtime partner, Sarah Pavan, had decided it was time to go their separate ways.

“That was never on my radar until it did show up,” Wilkerson said of the possibility to team up with Humana-Paredes. It took some time for her to decide to switch partners for the second time in a year “but I wanted to trust my intuition, trust what my plan was.”

Their plans for 2023 are straightforward: play in “pretty much everything” to put themselves in a position to qualify for Paris 2024 via the world rankings when they close next June. The biggest event on their calendar is expected to be the FIVB Beach Volleyball World Championships in October.

While she has new career goals, Wilkerson isn’t losing sight of personal goals she has set for herself.

A big one is to represent the BIPOC community, particularly the culture and ancestry from which she, identifying as a biracial woman, comes.

“Representation is important because it opens the gate for limitless opportunities,” she said. “Sometimes it’s hard to see yourself somewhere because it hasn’t happened yet, but I think it’s all of our responsibility to break those barriers and to do our part to make sure that everything imaginable is accessible. There’s a beauty in being able to dream big and to be a first and to open up those spaces that were not open before.”

READ: How 2020 was a year for Brandie Wilkerson to learn, reset, and find her voice

Since rising to the ranks of one of the top beach volleyball players in the world, Wilkerson says she’s had lots of little girls of mixed race tell her she is their favourite player because they can visualize themselves in her.

“That is so empowering. It just fuels my fire to keep going and to have it cross genders.”

Wilkerson is also giving a boost to the next generation through Project Worthy, a scholarship program she started with best friend and former beach volleyball partner Julie Gordon. With an eye on making volleyball a more diverse sport, each season they directly support one teenage indoor player from the BIPOC community by covering their costly club fees. They’ve funded three recipients so far and hope to grow it further.

“The only reason why I could start playing volleyball is because someone else took care of my fees, someone else bought me shoes, someone else bought me knee pads,” said Wilkerson. “When the problem seems so big and you’re talking about equality, you’re like, oh my God. So, if we could just do one little thing to help, that’s where it came from.”

One other thing that has Wilkerson super excited is she is soon to be revealed as the global face of a multi-million-dollar American sports brand, making her the first volleyball athlete to have both a clothing sponsor and a ball sponsor.

“They’re willing to put my face out there and my face being a biracial face, a Canadian face, a multicultural face and allowing that to represent beach volleyball, the sport.”

It’s a breakthrough moment that has been a long time coming.

Cédric Fofana: Finding the good in the bad

Fofana was just 17 when he earned Canada’s lone Olympic berth in the men’s 3m springboard for Tokyo 2020. Having gone into the national trials under the radar with zero expectations of himself, he came out of them with the top score.

“It was a bit of a shock for me, because I wanted to go but at the same time, I didn’t think I was gonna go,” said Fofana. When he had moved to Montreal in 2017 to train with the nation’s best divers, Paris 2024 and Los Angeles 2028 were his targets.

“But then I just kept progressing really fast… and yeah, it happened.”

Fofana has been diving since he was six, three years after he first spotted springboards while on a swimming outing with his parents. He told them: “When I’m older, that’s what I’m gonna do.”

Though his father Souleymane, who immigrated from Côte d’Ivoire in 2000, tried to get him interested in other sports like soccer, Fofana only needed one game on the pitch to realize he belonged in the water.

He dreamed about becoming an Olympian from the time he was nine. But what he experienced in Tokyo was closer to a nightmare.

His longtime coach César Henderson could not be on the pool deck with him because of complicated logistics reasons. It was his first major international competition and the spotlight was intense – starting from the moment he stood alongside his competitors and the camera went down the line to introduce them to a global audience.

“It was really overwhelming to be there and to see everyone being so good,” Fofana reflected.

The stress he felt was like nothing he had felt before. He began to panic as he struggled to breathe and his legs shook. He had just 10 minutes to try to pull himself together.

It wasn’t enough time.

None of Fofana’s six dives went to plan, exemplified by his fourth which was a total miss receiving zero points. He finished last of the 29 competitors in the preliminary round.

Still, he has been able to find pride in the way he handled himself amidst such adverse circumstances.

“I didn’t want to stop mid-competition just because I failed the dive or nothing was going to plan,” he said.

His big takeaway from a disastrous Olympic debut: “I learned that it’s not only about performance, but you need to be mentally ready to perform when it matters. Because even if I was physically ready, I couldn’t perform under that pressure. And that’s something I need to work on, so that’s why I kept coming back.”

Fofana is trying to get used to being nervous by competing more in smaller competitions. He admits that though he trained well leading up to last summer’s Commonwealth Games, the event still stressed him.

He’s looking to gain more experience this year by qualifying for the World Aquatics Championships and the Pan American Games. To achieve those goals, he is working on more difficult dives, which are made more difficult for him because of his tall height.

Fofana would love nothing more than to be part of the new generation of Canadian divers who have stepped up to fill the void left by the retirements of Meaghan Benfeito and Jennifer Abel, who was almost a big sister to him.

For years, Abel was among the few divers of Black heritage at the top international level. Although diving’s lack of diversity hasn’t been a big topic at home, Fofana says his family is proud that he represents the Black community in his sport.

“My dad is like ‘When you’re on the board, it shows that you’re an African, that you have African roots’, because he says that African athletes are emotional. And he says, ‘You’re a really big African because you dive with emotion and it shows’.”

Last summer, Fofana met his grandparents in Côte d’Ivoire for the first time in real life. It was an eye-opening experience. But it was a trip that made him feel more connected than ever to the culture he represents.

Joshua Liendo: Taking the next step

Just a few months after his Olympic debut, Liendo became the first Black Canadian swimmer to win a gold medal and/or an individual medal at a major international meet. He did that at the short course world championships in December 2021.

But in the summer of 2022, he really “nailed the goals” he had.

Liendo won three medals at the long course World Aquatics Championships, including individual bronzes in the 100m freestyle and 100m butterfly. It had been almost five decades since a Canadian man last stood on the world podium in the latter. He followed up with four medals at the Commonwealth Games, highlighted by his gold in the 100m butterfly.

“I showed that I was able to, at the big moment, [make the] final in these events. I was able to step up and do what I’m supposed to do,” reflected Liendo.

It had been seven years since Canada had won a world championship medal in any men’s swimming event. In the intervening years, the women’s team became one of the most competitive in the world, led by the likes of Penny Oleksiak and Kylie Masse. Even though he is still just 20, Liendo is not afraid of being the instigator for the men’s national team.

“The guys who have experience on the world stage, I feel it’s our job to get the younger guys or bring a group of us together to get in the mindset of we can win medals and we can be just as competitive,” said Liendo. “We’re on the come up now, which is great.”

In the fall, Liendo moved from Toronto to Gainesville, Florida to attend the University of Florida. He has decided to major in applied physiology and kinesiology. For his freshman year he took four courses each semester, a mix of in-class and online learning, as he balances being a student and an athlete.

While he had to leave behind the elite training environment at Swimming Canada’s High Performance Centre – Ontario, he joined another top tier program led by head coach Anthony Nesty. The 1988 Olympic champion in the 100m butterfly while representing Suriname, Nesty was the first Black swimmer to win an Olympic gold medal.

His experience and success as a competitor and coach was a key factor in Liendo’s decision to continue his development down south. That they are both minorities in a predominantly white sport helped forge a different connection.

“He’s been through it all,” said Liendo. “Having someone that I can relate to like that, he understands. Obviously, we talked and especially now in the sport we’re seeing more Black swimmers excelling, which it’s great to see the sport getting more diverse.”

While growing up, Liendo watched Olympic swimming races because he swam, but he never really saw someone he could relate to. Instead, he found inspiration in Black athletes from other sports, such as NBA star Allen Iverson.

“I love watching talent and watching greatness,” he said.

Now that he can be that representation for other young Black swimmers, Liendo has found it to be an adjustment.

“At first I was like, whoa, people are looking up to me now, which I found almost strange in a way… Now I’m grateful for all the support that I’m getting and all the people that look up to me and say, ‘You know, I have a kid that looks up to you and now they know they’re not alone’. It’s a great feeling and it’s humbling to know that I’m in that position,” he said, adding that the nice messages he receives on social media give him extra motivation.

His training mates in Florida also provide a push as he prepares for a busy few months that include the NCAA Championships followed almost immediately by the Canadian trials at which the world championship team will be decided.

“There’s always someone that’s doing something great, that’s world class at what they do. There’s always someone to race and someone to look at to push myself even further,” Liendo said, noting he has gained a different perspective on his sport.

“It’s specific things getting better, small details. I’ve been working a lot in the weight room down here… I’m kind of surprised at how much more I still need to learn in this sport, but it’s also exciting to know that there’s areas to improve on.”

If there is one thing for certain, it is that Liendo will not be resting on the laurels of what he has already accomplished.